Business Week 29 Sept. 1997 pages 32-33 By Larry Armstrong in Los Angeles, with Elizabeth Veomett in New York and bureau reportsSouthern Californians, jittery about predictions of an unusually wet winter, braced themselves as Hurricane Linda, the strongest-ever-recorded Pacific hurricane, raced up the Mexican coastline. In Malibu, the city ran out of the sandbags it hands out to residents to protect their homes from mudslides and flash floods. Bulldozers in Hermosa Beach built eight-foot-tall sand berms to protect coastal buildings.

Linda blissfully headed out to sea on Sept. 14, leaving only a gentle

onshore rain that put out a fire in the San Bernadino Mountains. But

Californians aren't letting down their guard. Linda was a by-product

of El Nino, a phenomenon that arises in the Pacific every two to seven

years and alters weather patterns around the world.

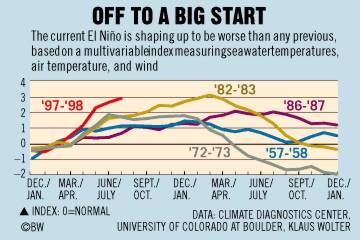

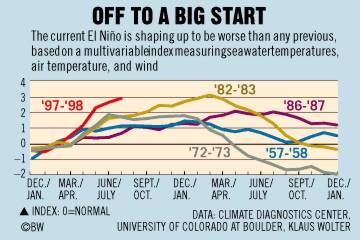

This year's El Nino promises to be a whopper, already exceeding the

intensity of the 1982-83 El Nino at its peak (chart). Forecasters

warn Californians to expect as much as three times normal rainfall

from January through March. Even now, El Nino is wreaking economic

havoc throughout the world, causing droughts in Southeast Asia and

Central and South America.

The last big El Nino, the 1982-83 one, caused more than $8 billion

worth of damage worldwide--equivalent to $13 billion in 1996 dollars,

according to U.S. government estimates. ``We are preparing for the

worst,'' says Douglas P. Wheeler, California's Secretary of Resources,

``and hoping for the best.''

El Nino, ``Christ Child'' in Spanish, was the name Peruvian fishermen

gave the warm currents that would show up every few years just before

Christmas. Most years, trade winds blow across the tropical Pacific

from east to west, piling up as warm surface waters off Asia. But

when those winds slow or reverse direction, the water sloshes back

and the world experiences an El Nino event.

This year, the ocean along the west coast of South and Central America

is as much as five degrees above normal. As a result, Central and

South American countries are experiencing storms and flooding in some

places, drought in others. Already, Peru has declared a state of emergency

for more that half of its land. It expects El Nino to cause up to

$1.2 billion in damage and knock the growth of its gross national

product down two points, to 5% next year.

El Nino is wreaking havoc with Peru's exports, a key source of economic

expansion for the country. Peruvian Central Bank chief German Suarez

Chavez predicts that fishmeal shipments, based on the anchovy catch

and the country's largest export, will drop 43% next year. ``Warmer

ocean temperatures have driven the anchovy fleet into deeper water

or south toward Chile,'' says Alejandra Martinez, a researcher at

Geophysics Institute of Peru. That stands to have a ripple effect

worldwide because soybean prices will rise as farmers search for alternate

protein sources for animal feed.

FLOOD AND DROUGHT. Meanwhile, northern Peru is gearing up for torrential

rains. The country has already spent more than $20 million reinforcing

bridges, clearing rivers and canals, and upgrading drainage systems.

The government is encouraging farmers to plant rice instead of the

usual cotton, even though that means it will have to import 20% more

cotton to supply the country's textile mills.

Guatemala and Costa Rica have also declared states of emergency. Guatemalan

authorities say that 40% to 50% of the country's corn, bean, and coffee

crops have been lost to the summer drought. In Costa Rica, 25% of

the rice crop has been lost, and coffee production, which accounts

for 8.9% of the country's exports, may be down as much as 40%. ``It

has gone from an agricultural problem to a national problem,'' says

Ricardo Garron, Costa Rica's agriculture minister.

Things aren't much better on the other side of the Pacific. Deprived

of the warm water that fuels monsoons, Australia, Indonesia, and the

Philippines are suffering severe droughts. The Australian Bureau of

Agricultural & Resource Economics predicts that drought on the east

coast will wipe $1.4 billion off of crop exports, based on a 12% drop

in production. It expects the wheat crop, the country's biggest commodity,

to be off 30%.

In Indonesia, President Suharto in late August warned of a possible

food shortage if the rainy season is delayed three months, to December,

as Indonesia's Meteorology & Geophysics Agency predicts. Rice paddies

started drying up in early August, the corn crop has been savaged,

and this year's coffee production is down 30%.

El Nino is usually a mixed bag for the U.S. In general, El Nino appears

to nudge the jet stream to the southeast, where it can better drive

off hurricanes. That also makes for warmer, drier winters in the North

and warmer, wetter winters--and possible flooding--in Southern California

and the Gulf Coast. In the 1982-83 El Nino, floods did $1.2 billion

worth of damage, and the following year's drought cost farmers $10

billion, but consumers in the Northeast saved a tidy $2.5 billion

on heating bills. With El Nino's effects rippling across the globe,

Congress held hearings on El Nino on Sept. 11.

Farmers and commodities brokers have long paid attention to El Nino's

progress. Prices of futures contracts for cocoa, coffee, wheat,

and corn are already on the rise. And this year, executives from all

sorts of businesses are paying attention, too. ``If the winter is

warmer, it will drive down fuel costs,'' says John H. Dasburg, president

and CEO of Northwest Airlines Inc. ``When we look at our hedging strategy,

we factor in El Nino.''

Scientists have come a long way in predicting the onset of El Nino

since the 1982-83 occurrence, which caught the world by surprise.

Relying on data from weather buoys in the Pacific and computer-modeling

techniques, the National Weather Service began warning about this

year's El Nino five months before its effects were first felt.

Still, it's difficult to make plans based on weather forecasts. Everyone knows that just because the TV weatherman predicts a 70% chance of showers you may not actually need an umbrella the next day. Ask Craig Underwood of Oxnard, Calif. He lost 8 of the 250 acres he had been farming when a swollen river undercut his property during the last big El Nino. However, he's not panicked about this year's El Nino. ``Some farmers are tempted to adjust their planting plans because of El Nino,'' he says. ``It's too risky, because you never know the timing of weather.'' Live and learn.

Copyright 1997 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.

Return to Recreational Boat Building Industry Home Page